INTRO

In 1773, Samuel Johnson paid tribute to his travel companion on what he presents as a greatly anticipated journey to “the Hebrides, or Western Islands of Scotland.” He finds in the young James Boswell “a companion, whose acuteness would help my inquiry, and whose gaiety of conversation and civility of manners are sufficient to counteract the inconveniences of travel, in countries less hospitable that we have passed” (35). As Boswell and Johnson set out from Edinburgh, they were alone except for Boswell’s servant, “Joseph Ritter, a Bohemian,” as Johnson “thought it unnecessary to put himself to the additional expense of bringing with him Francis Barber, his faithful black servant,” a subject now of a magnificent biography (Michael Bundock, The Fortunes of Francis Barber, Yale UP 2015).

Our group consisted of thirteen. Our age ranges closely paralleled the difference between Boswell and Johnson’s. Our trip necessarily was curtailed by the time limits of spring break, travel safety stipulations especially in early March (Boswell and Johnson travelled for two months beginning mid-August), and the practicalities of mobility with a much larger group, even if we did have the conveniences of hotels and trains. Most of us were newly acquainted, not friends of ten years with similar cultural perspectives and backgrounds. Yet, the same acuity of observation, gaiety of conversation, and civility of manners that Johnson boasted of more than made up for the inevitable inconveniences of travel and led to memories as lasting as the pictures we took of the stunning Scottish countryside.

Just as Johnson’s interest was in the “men and manners” of a remote country, so our city dwellers were eager observers of what had seemed an almost mythical place and entered with the “wilds” of America as points of comparison. Like Boswell, my main interest was my fellow travelers as they encountered Scotland and its people. I have done these concentrated study abroad trips a couple of times before, but this one, mimicking a classic travel narrative with the purpose of discovery and engendering travel narratives, worked exceptionally well. Even the unpredictable, I realized, could bring us closer to the spirit of Boswell’s and Johnson’s tour if further from the actual path that they took.

This space is to allow the students to relate their experiences. I want to conclude, however, with a couple of pictures that illustrates the trip on which we followed Boswell and Johnson into Edinburgh and Glasgow and some of the Highlands. I also want to relate a moment that captures the fellowship that Boswell reveled in and that made the trip special in his time and ours.

Boswell dwells repeatedly on the weather and the way it impedes their journey. A little paranoid that anything could go badly awry, I was especially concerned about bad weather for this trip. In fact the gods smiled upon us with mostly lovely sunny but cold days; however, my fear seemed validated when about half of us stepped out of the airport on arrival into pouring rain. By the time we got to our AirBnB, we were soaked and freezing cold. Greeting us were those who had arrived first, figured out the complicated entry system, but been unable to operate the unfamiliar furnace to trigger the radiators. Boswell thought fit to record the comic but touching sight of Dr. Johnson lying in straw in a hut in the outer Hebrides. So for me, a lasting memory will be entering the apartment to find three of the group huddled in beds for warmth in coats, scarves, mittens, and hats, and comforters pulled up to their noses.

These trips would not be possible without the generous support of the Department of English, the Dean’s Office, and the Study Abroad Office at Georgia State University. –TMC

MARIA’S RESPONSE

First this, biggest that, deepest this, highest that. The list of Scottish superlatives we heard from tour guides throughout bonny Scotland was staggering. Was this simply rhetoric? “Visit Scotland” marketing? Or the real deal? Who knew Scotland is such a hub of – everything? No wonder Boswell was so keen on Johnson coming for a visit. He was justifiably proud, as was just about everyone we met. Here’s a sampling of the impressive Scottish facts we heard, and some Snopes-style clarification/substantiation:

- The National Library of Scotland is the largest research library in Europe. This “fact” from our wonderful librarian tour guide is not quite right: The library’s web site calls it “one of the major research libraries in Europe.”

- Scotland is home to the largest arts festival in the world, the Edinburgh Festival Fringe. Our librarian got this right: In 2017, the festival spanned 25 days and featured 53,232 performances of 3,398 shows in 300 venues. I want to go!

- The first international football match was held in Scotland. Tour guide Ian was correct; he even (impressively) got the date right: 1872. Scotland vs. England in Partick. Interestingly, it was a 0-0 draw, watched by 4,000 spectators.

- Scotland has the UK’s deepest and longest lakes (lochs). Stewart gave us legit info: Loch Moraris the deepest of the UK’s lakes and Loch Awe the longest.

- Ben Nevis is the UK’s highest mountain. Right again, Stewart! At 4,411 above sea level, it’s covered in snow for seven months of the year.

- Scotland has a rich history of medical research. Literary tour guide Alan did not exaggerate. In fact, a walk through Edinburgh’s History of Surgery and Pathology museums are incredibly impressive, as Kathryn and I can attest. We could have spent an entire day; but be warned: The pathology museum, one of the largest collections of pathological anatomy in the world, is not for the squeamish – think actual aneurysms, tumors, and eyeballs, preserved in formaldehyde for posterity. As Alan shared, Scotsmen Joseph Lister discovered antiseptic and James Young Simpson discovered chloroform as an anesthetic. And then there’s surgeon Joseph Bell, the inspiration for Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes. Scotland truly is a medical hub: Today, over 30,000 people are employed in 600 life science organizations across Scotland, according to a November 2017 article in The Scotsman. And don’t forget, Dolly the sheep was “born” in Scotland; she was the first mammalian clone created from adult somatic cell.

- Presbyterianism originated in Scotland. As a Presbyterian, I knew this to be true, but had it confirmed by the kind clerk at the Glasgow Cathedral, where Presbyterian services are held every Sunday. Most of this beautiful medieval cathedral, originally Catholic, was built in the 1200s. The “official souvenir guide” I purchased says it was “substantially enlarged in the 13th [century], it survived the Reformation almost intact and stands today as the most complete medieval cathedral on the Scottish mainland.”

One intangible Scottish superlative is its collective personality. In other words, its cheerful, friendly, helpful, charming people. Without exception, Scots are lovely, to British-ize my descriptor. When I commiserated with Ian, one of our tour guides, about America’s current political situation, he sought to comfort me by reminding me of the dismal state of British politics. He spoke to us about the prejudice of the English against the Scots, and educated us about the referendum for a separate Scotland. Looking in on Scotland from the outside, the people seem united in their pride for their country. I was jealous; Americans have never been more divided. During a heartfelt conversation with Dionne and Raniqua during which they shared their fears about being black in today’s America, I fought back tears. I realized that what hurts me most about today’s America is not so much who is in power, but who put him there. As Andrew Sullivan recently wrote in the The New York Times Book Review, “You can impeach a president, but you can’t, alas, impeach the people. They voted for the kind of monarchy the American republic was designed, above all else, to resist; and they have gotten one.”

Sometimes it takes traveling somewhere far away to gain perspective on things close to home. Thank you Dr. Caldwell and Georgia State for affording me yet another opportunity to broaden my horizons and expand my mind. I am forever grateful.

DEEDEE’S RESPONSE

Stories of Women

Samuel Johnson, James Boswell, Robert Louis Stevenson, Sir Walter Scott, Robert Burns, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, and more… I certainly knew that the circumstances of history privilege the stories of (white) men but, as with other experiences on this trip, my first-person encounters allow this message to resonate more fully than my simple knowledge alone. Let me then focus on three women whose stories have made their way to me across the centuries and though my travel experience in Scotland.

Mary Queen of Scots was mentioned frequently on our tours, but what of, what one tour guide called, “the other Mary”—textile proprietor at King’s Close in the seventeenth century? I love that some of her story has survived (and continues to evolve through research) and that the details of her existence (and others like it) are celebrated through an historic tourist attraction. Mary King was a widow, a mother of four, and merchant who lived and worked in the King’s Close area of Edinburgh. We know when she was married and widowed, the names of her children, the location of her booth in the close, and we have a list of items that she owned at the time of her death. We also know that eventually, Mary King became so well known that the area known as King’s Close began to be known as Mary King’s Close. Mary King’s legacy was not logged into written or oral history as Mary Queen of Scots’ was but, doesn’t that make it even more remarkable? One hard-working woman forged a life for herself and her family in desperate times and circumstances: human and real. I am thrilled to have a glimpse of her story.

I was also fortunate to see a Scottish adaptation of English playwright Hannah Cowley’s The Belle’s Stratagem at the Royal Lyceum Theatre. Although I enjoyed the production, the most striking element of the evening was learning about the playwright, herself. The playbill tells us that Hannah Cowley broke social norms to become a successful playwright in eighteenth century London. Her plays often featured witty (sometimes risqué) comedy and a smart woman in the leading role. Cowley often had to fight fiercely to see that her work made it to the stage. Even more surprising than the story of Cowley’s success, is the story of how she later tried to hide that she had earned it. After fighting for her work for years, Cowley eventually left London life to retire to her tiny hometown of Tiverton. There, she strategically worked to rewrite her own life story to eliminate her playwriting success and to focus on her role as a respectable wife and mother. It is only through careful, persistent scholarship that Cowley’s true story has been recovered. I realized that women often published anonymously or under male pseudonyms, but I had not considered that, once achieving success, they may prefer to take that success to their graves. How many other Hannah Cowleys await recovery in the years to come?

Last, but not least, this course led me to the celebrated Jacobite heroine, Flora Macdonald as related by James Boswell and as told to us centuries later by our Rabbie’s Tour guide. In A Journal of a Tour of the Hebrides, Boswell describes Flora Macdonald’s genteel appearance and sense of humor, but as he tells of her role in Prince Charles Stewart’s escape from the English, and of her clever rescue of a fellow Jacobite from a London prison, we know that her story did not survive the centuries due to her gentility and wit. If her story is true (although she has become the stuff of legend, a quick Google search reveals that historians agree that she assisted Prince Charles), Flora Macdonald was a true role model for loyalty, intelligence, and bravery. In fact, each of the women’s stories I encountered on this trip reveal its own heroinism. From a humble mother and merchant, to a successful but conflicted artist, and a fearless highland rebel, I raise my glass and toast to the stories of these women. Sláinte mhath!

SHEILA’S RESPONSE

Following “in the footsteps” of Samuel Johnson and James Boswell invariably includes evidence of the chronological expanse separating the 18th and 21st centuries. Nowhere is this more evident than on modern treks to Loch Lomond. When Dr. Johnson describes the intrepid duo’s sojourn there, he focuses first on its socially significant inhabitants: “From Glencroe we passed through a pleasant country to the banks of Loch Lomond and were received at the house of Sir James Colquhoun, who is owner of almost all of the thirty islands of the Loch” (Levi, Kindle location 2888). He then offers disparaging comments about the region’s climate and topography: “Had Loch Lomond been in a happier climate, it would have been the boast of wealth and vanity to own one of the little spots which it incloses (sic), and to have employed upon it all the arts of embellishment. But as it is, the islets, which court the gazer at a distance, disgust him at his approach, when he finds, instead of soft lawns and shady thickets, nothing more than uncultivated ruggedness” (Levi, Kindle location 2888).

Today, visitors find much more to admire about the scenery on offer here, but the Loch Lomond segments of our two Rabbie’s tour stops there (www.rabbies.com) were focused largely on the Scottish nationalist sentiments generated through powerful modern renditions of the classic nineteenth century song, “Bonnie Banks ‘o Loch Lomond.” Both tour guides presented emotionally charged narratives about the historic events alluded to through the lyrics of the piece and used these musical selections to support their impassioned defenses of Scottish independence.

While this iconic song had not been written when Johnson and Boswell visited the area, the Jacobite rebellion, which it commemorates, had already occurred. Indeed, as Peter Levi notes in the introduction to his dual edition of Johnson’s A Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland and Boswell’s The Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides (London: Folio Society, 1990), these tumultuous events of the mid eighteenth century nearly derailed the impetus for this duo’s journey through the region: “this expedition was an old project. It matured almost too late, because the war of 1745 was the beginning of the end of ancient Scotland, and the processes of change in the Highlands were already gathering speed” (Levi, Kindle location 122).

Although Boswell was famously supportive of Corsican independence, the prospect of political sovereignty for his native land seems not to have captured his imagination as fiercely as it has engaged our modern Rabbie’s guides. For Dr. Johnson, Loch Lomond signaled societal prosperity and unrealized geographic appeal. Scottish separation from England was not on his mind. For our tour guides, however, the same location offered opportunities to share poignant hopes for an independent Scotland. While the landscape has not changed inordinately, its disparate political and social resonances for each audience demonstrate the considerable distance marking the difference between these notable eighteenth century visitors and modern international tourists as they approach the “bonny banks” of Loch Lomond.

RA’NIQUA’S RESPONSE

“Novelty and ignorance must always be reciprocal, and I cannot but be conscious that my thoughts on national manners, are the thoughts of one who has seen but little” (Johnson 151).

Upon arriving for the first time to Loch Lomond, fourteen miles north of Glasgow, our van stopped at a small café near the shore. I had checked the weather that morning. The temperatures would hover around 8 degrees Celsius, about 46 degrees Fahrenheit back in the States. I was not accustomed to making this conversion, nor was I accustomed to the new time zone. Nine in the morning in Scotland was only five in the morning back home in Georgia. Groggy and cold, I climbed down from the van that had brought us out of Glasgow. Some of our class went straight for the lake, where the water sat still and reflective, but I stopped in the café and purchased a small green tea, piping hot and filled to the brim. I carried the steaming cup down to the dock, watching the lake reflect the sky. For the moment, I allowed myself to forget America.

Forgetting America turned out to be quite the task. Johnson’s comment about novelty and ignorance hints at the inherent biases we all carry with us. These biases are shaped by our experiences. To have experienced little is to be in awe at everything. Before landing in Scotland, I had never traveled abroad and so I found novelty everywhere, even in the familiar. Our class arrived in Edinburgh, a city Samuel Johnson deemed “too well-known to admit description” (Johnson 35). I won’t describe the city either but for a different reason. I don’t have the words. That first night, we had dinner in The Theatre Royal Bar, a small bar a short walk away from Edinburgh Playhouse. Inside, playbills from American musicals covered the walls, and as the group debated placing an order for haggis, Rihanna’s “Rude Boy” played over the speakers. I knew not to be surprised by this, having read about the pervasiveness of American culture in other countries, but I did wonder if this was how the Scottish saw Edinburgh or of this was just the Edinburgh being offered to me, an American tourist who might never know the difference.

While in Edinburgh, we sought the historical and there found a world before Hollywood and Rihanna’s Good Girl Gone Bad. We toured Mary King’s Close, the remnants of seventeenth century Edinburgh housing hidden beneath the Royal Mile. The squat rooms of the close resembled caves. Any windows looked out onto alleyways now covered by more modern buildings. Our group crowded into one room while the tour guide told us about the reoccurring outbreaks of the Black Death, which claimed a third of Edinburgh’s population and eventually prompted endeavors to build new, more sanitary housing. We later took a literary tour around the city in which we heard about such writers as Robert Burns, William Ernest Henley, Robert Lewis Stevens, and Arthur Conan Doyle. As we walked around the city learning about Burns’s Clarinda, Henley’s extended hospital visit, and Doyle’s failed career as an eye doctor, I didn’t think much about the Subways, the McDonalds, or the Pizza Huts, but they were there and they were thriving.

Even in Loch Ness, I couldn’t fully forget America, although the lake was beautiful. It didn’t have the same reflective quality as Loch Lomond, but the darkness of its surface paired with the legend that made it famous gave the lake a mythical quality that left me just as awestruck. Right before our group departed from Loch Ness, however, our van got a flat tire, which meant that we had an extra hour to spend in town. This was fine with me. I’d set out on the trip to find gifts, specifically mugs. I wanted mugs that I couldn’t buy anywhere other than Scotland. That left me doing quick sweeps of every store I entered and making beelines for every coffee mug display. Often, I would find a nice-looking mug, turn it over, and discover that it had been made in China. Then I would be forced to leave the mug and the store behind. This was my experience with The Millshop, a small touristy gift shop near Loch Ness. I left empty handed with another forty-five minutes to kill. Ben, Kristen, Maria and I wound up wandering around an old Abbey. Initially, I refused to go onto the property because of my American understanding of trespassing laws. In America, a fence usually indicates that one should keep out, but we were in Scotland, and American trespassing laws did not apply.

Eventually, I realized that I wasn’t so much finding America in Scotland as I was finding it within myself. I had carried it with me. It was my impulse to seek out signs of my culture in the hopes of finding a link between myself and a new one. Maybe this is an impulse that is present in us all. There are universities in both Edinburgh and Glasgow. Campus culture in Scotland differed from campus culture in the States if for no other reason than the fact that Edinburgh University had a bar on campus. Ben, Kristen, and I poked into Library Bar after visiting Edinburgh Castle to discuss our experiences in Scotland. It was our last night in the city, and we had seen so much. At this bar, we discovered a live music space where college musicians were putting on a concert. At the end of the concert, we talked to one of the performers, who was overjoyed to hear that we liked his music and happy to know that he now had fans in Atlanta. We said we would look out for him if he ever had a show in the States. We would be his link across the Atlantic.

Before leaving for Scotland, I was nervous. As a black woman, I am used to being a minority in the bubble that is academia, but at 25 Park Place, we are in a bubble in the middle of one of the most diverse cities in the United States. I think I held on so tightly to my American identity in Scotland because I was afraid of being untethered in a place where ninety-six percent of the population identified as white. Although I did get some stares, everyone I encountered was kind and welcoming. I have found that no matter where I go there is nothing more powerful than coming face to face with someone, acknowledging his or her difference, and choosing to say, “Hello.”

BEN’S RESPONSE

In 1753 a section of old Edinburgh still survived as a slum and was used as the foundation for the expansion of the Royal Exchange, now the City Chambers. The construction covered over the old city to build a marketplace for modern city life and exchange. On our guided tour, we entered though a shop and walked down a series of narrow stairways leading us to Mary King’s Close, a section of the old city preserved beneath the Royal Mile. The section is named after a fabric merchant who started her own business after her husband died. The construction of houses was cramped with houses built upward on top of each other with narrow passageways between. At the time it was inhabited, the tall packed in buildings blocked the sunlight from reaching individual houses and the street, and only the wealthier inhabitants were able to have access to sunlight in their homes by paying to knock down nearby houses. Over 30,0000 people lived in a few square miles and when the bubonic plague hit in 1645, a third to half of the residents died. The living conditions were unsanitary. People would empty their chamber pots twice a day at scheduled times and their waste would flow down the streets into Nor Loch.

As we walked through the houses and narrow streets, the guide described to us the impact of the plague. He described how the infection spread from rats to humans by fleas that lived on the rats and also bit humans. Boils would break out on the sick person’s skin and infection would enter the blood stream, causing the body to become septic and eventually leading to death. The doctor who treated the plague victims wore an ominous mask with strong smelling herbs in the long phallic nose and a thick heavy cloak and hood to prevent his skin from being exposed to fleas. He treated the patients by piercing and draining the buboes—the swollen, puss infected lymph nodes—to prevent them from rupturing on their own and spreading the infection to the blood stream. He would then cauterize the wound with a hot iron. For this difficult work, the city council promised him a large salary with the expectation that he would die and they wouldn’t have to pay. However, he did survive and it took a number of years of legal action in order to have the full sum given to him.

The tour guide encouraged us to think of all the deaths of the plague as the inspiration for the reforms that brought about the Enlightenment in Edinburgh—the great medical school, the advances in antiseptics, the discovery of chlorophyll, thinkers like Adam Smith and David Hume, Dr. Joseph Bell whose methodical approach to medicine inspired generations of students and the character Sherlock Holmes—all of it growing from the death and unsanitary conditions and disease of the 1600s. But this destruction of the old city is also a form of preservation. Like the section of Mary Kings Close, the old city was sustained beneath the new Edinburgh that began in the 18th century. The obsessive need of the institutions of the new Enlightened city to rationalize, to order and arrange the world was driven by the fear of this irrational past. In this way, the old city continued to haunt Edinburgh as the spectral presence of all that it wished to exclude.

The Enlightenment’s compulsion to order and rationalize rears its head in Edinburgh author, Robert Lewis Steven’s 19th century novella Jekyll and Hyde. All the latent desires Dr. Jekyll represses to represent himself as a respectable man of science and social stature leads to the strengthening of destructive impulses that become manifest in the alter-ego Mr. Hyde. When Dr. Jekyll becomes unable to control his transition between Jekyll and Hyde both are brought to their death at the gallows that Dr. Jekyll created. The rational obsession to rid society of its unsanitary aspects and to correct humanity, represented by Dr. Jekyll, entails the death of both personalities. The desire to create the world in a rational image is revealed to be a form of the death drive, a destructive impulse and desire for the elimination of the self. Thinking about these two images of Edinburgh old and new, we get a fuller picture of the city and its history, not just the way the city’s reforms initially represented themselves but also in the aspects that the narrative initially attempted to exclude. Rather than an attempt to hide the rough history, we got the opportunity to see all aspects of Edinburgh and to understand its multiple narratives and dynamic conceptions of self.

TANYA S.’S RESPONSE

Though I have spent time in England in the past, this was my first time in Scotland, and I was never before aware of the pride Scotland takes in its literary heritage. The literary tour guide, Alan, spoke at length about Robert Burns and Sir Walter Scott, and the pub tour guides also spoke of both, and also Robert Louis Stevenson. The huge, Gothic-looking monument to Sir Walter Scot, its spire making it visible from a great distance, also advertises Scotland’s deep pride in its literary heroes.

Still, although we were on the trip for literary reasons, and I learned much about Scottish writers and bards, I found the nationalist spirit in Glasgow one of the most interesting things about the trip. The spirit of literary pride is also alive and well in Glasgow, as evidenced by the statue of Robert Burns that stands high on a pedestal in George Square. There is a nationalist vibe in Edinburgh as well, but in my view, Glasgow has a special energy. As a reader of George MacDonald novels, I have long known something of the Scottish spirit of fierce independence and defiance, and it is tangible to this day. If Johnson seemed a bit disappointed at the lack of perceived fierce, militant Scottish spirit in his encounters with the Scots, I felt no such disappointment. The Scots may be civilized by English standards, but they have not been brought to heel. In Edinburgh, I noticed immediately the many Scottish flags that were proudly displayed on and near businesses and in public areas; some were hung by themselves, and some along with Union Jacks. In Glasgow, the Scottish flag was flown as well, and it seemed to me that it was accompanied by the Union Jack less often. Moreover, I saw Scottish flag stickers stuck on public buildings and objects in a way that would be described by some as graffiti, but I saw it as more of a tongue-in-cheek defiance. One Scottish flag sticker was stuck on the arse of a naked bronze statue, and I took this to be a form of nose-thumbing at those who would keep Scotland bound to the United Kingdom (I am mad at myself now for not getting a photo).

There is another symbol of Scottish defiance in Glasgow, on Royal Exchange Square: a statue of the 1st Duke of Wellington, looking heroic and powerful on horseback, with a plastic traffic cone on his head. When I first saw it, I thought it was just ordinary vandalism, but when I saw t-shirts featuring photos of the statue and cone in a museum shop, I knew it was more than that. The shop girl explained to us that the cone began to appear several decades ago. The city council would remove it, but within a few days, a new cone would appear. Due to public outcry, plans in 2013 to raise the statue high enough to eliminate the statue-coning were scrapped, and the cone was allowed to stay. The fact that the people of Glasgow actively campaigned to keep this quirky bit of their culture says a lot about their independent spirit.

The nationalist notions symbolized by the Scottish flags were made more concrete by the tour guides who took us to Loch Ness and Loch Lomond. Stewart and Ian, the guides, both expressed nationalist views and a desire to be independent from Great Britain, but Ian was particularly passionate. He spoke at length of the English abuses of the Scottish over the centuries, and was also quite eloquent about Scottish literature. Announcing that he is a descendent of Robert Burns, Ian told stories of the poet, including the tragic fate of his first love, Highland Mary, and Burns’ unconsummated relationship with the married woman he called Clarinda. Though we had heard about Clarinda before from Alan, the literary tour guide, the story seemed more authentic and moving coming from Ian, with his long, unkempt gray hair and gruff passion for his country.

There is so much more to discuss, but I am afraid I am running on too long, and I want to at least mention my experience at the University of Glasgow, where I was privileged to handle and read the original letters of George Jardine to his associates. The woman at the Special Collections desk at the University library was extremely helpful, setting me up with a temporary access code to the library network so I could browse the catalog to choose the letters I wanted to read before requesting them, and thus make the most of my time. It was truly fascinating to read the script of a writer who has been dead for nearly two centuries, and glean his thoughts about academic issues as well as political issues, such as Napoleon’s conquests and riots that took place at the University in 1804. Because the script was a difficult to read and there as such a wealth of material, I knew it would take several days to find what I needed about the early Moral Philosophy courses that required writing. I did not have the time required on this trip, so I have decided that I need to come back to Glasgow at a later date with more time and more prior reconnaissance to make my exploration of these archives as efficient as possible. I am glad that I got the opportunity to see the archives and collect the information that I did, and I am also glad that I have a great reason to make another trip to Glasgow!

Credits for attached photos:

Duke of Wellington statue photo attributed to: User Rept0n1x at Wikimedia Commons – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10645879

KRISTEN’S RESPONSE

On the tenth of March, we gathered in Edinburgh to follow in the footsteps of Boswell and Johnson. We wandered the hilly streets of Edinburgh and climbed the narrow closes; there were thirteen of us walking in a single file line or sometimes in pairs with luggage trailing behind us, experiencing the Edinburgh that, for Johnson, was a “city too well known to admit description” (35). The streets themselves were a description, an unfolding narrative of the historical and literary entwined with the modern and personal. We followed the routes of Google Maps, tourist maps, tour guides, and local recommendations—paths that often led to the unseen and unexpected. Our group descended into the hidden streets and houses of Mary’s King’s Close, haunted by the memories of sickness and persistence. We explored the endless levels of the National Library of Scotland where we made relations between dissimilar book titles that were stored by height: a biography of Mariah Carey sat alongside Jonathan Culler’s Beyond Interpretation. On the last night of our journey, a few of us explored the University of Edinburgh’s campus and encountered another “Underground,” an unsuspecting music venue at the end of a hallway that featured local musicians.

GLASGOW

Glasgow, like Edinburgh, was absent from Johnson’s account for “to describe a city so much frequented as Glasgow, is unnecessary” (149). Glasgow’s urban streets were highlighted by clock towers that seemed to draw the past into the present moment of our excursions: even the medieval cathedral was fitted with a timepiece merging the 15th century with our current time. Katherine and I walked along the river to Glasgow green and discovered large terracotta fountain made in a French Renaissance style in 1887 sat adjacent to the People’s Palace. It features the Queen of England at the top with sentries from Scotland, England, and Ireland directly below her. Oval cut-outs appear underneath the Queen and sentries and show figures representing four groups: Canada, South Africa, Australia, and India. The fountain, no doubt, acted as a celebratory symbol for the British Empire, which contradicted with the narratives of violence, oppression, and hopeful independence told by our tour guides.

GLENCOE

From Glasgow, we set off to the Highlands on a Rabbie’s bus tour. At Glencoe, we admired the dramatic scenery of the glens against towering mountain passes. Glencoe’s past was defined by the betrayal and murders of the Massacre of Glencoe in 1692 just after the Jacobite uprising; it was, according to Johnson, “a black and dreary region” (148). The tour guide explained that the Argyll soldiers (loyal to King James II) cordially lodged with the MacDonald Clan (who did not profess an oath to the King) for over a week until, suddenly, the soldiers turned on the MacDonald Clan and slaughtered several of their clan members. In the 1707 Act of the Union, Scotland combined with England to form the United Kingdom, which brought more tension between the Highland people and the British Empire. A sorrowful stillness filled the expansive grandeur and beauty of the landscape as if to memorialize its past inhabitants.

LOCH NESS

Loch Ness, one of Scotland’s largest lochs, holds mysteries in its muddied peaty waters. For Johnson, “Lough Ness well deserves to be diligently examined” (54). Today, the loch is “diligently examined” by hundreds of tourists that pile out of large buses to gaze over its waters. As we strayed from our tour bus to the shores of Loch Ness, a group of us explored the grounds of Fort Augustus Abbey, a nineteenth-century abbey that overlooks the loch. In 1998, the monks left and the Abbey closed, and in its place, now stands an exclusive Highland Club that offers luxury dining and accommodations along with recreational areas like tennis, croquet, and cricket courts. These recreational spaces are clearly marked on the Highland Club map; however, the map does not show the cemetery where the Abbey’s monks have buried for the last hundred years. The Abbey’s grounds tell the story of a town converted into a tourist hotspot—a place of religious dedication transformed into a place of amusement.

………………………………………………………….

In the words of Johnson, “Such are the things which this journey has given me an opportunity of seeing, and such are the reflections which that sight has raised” (152).

Works Cited:

Johnson, Samuel. A Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland, edited by Peter Levi, Penguin Books, 1984.

DIONNE’S RESPONSE

“A Sense of Place: Impressions of Space on Collective Memory and Identity”

I’m a southerner. I’m a Black woman raised in Birmingham, AL. The historical, socio-cultural, and political narratives and realities of my heritage cloak my consciousness and inform my cultural identity—within and outside of myself. So, when I began the graduate program at Georgia State University, I engaged with notions of place and it’s influence on memory and identity. Particularly, I approach my graduate work with these overarching questions: How does one – black, female and woman – see and relate to herself in all of her social, historical and cultural multiplicity in a vast sea of cultural representations? How does she journey and interact with the many social and cultural narratives that seek to define and explain her identity, subjectivity and place in Western society? Narratives of space, place, voice, and representation always seem to be my point of inquiry and entrance in every aspect of work that I participate in. As an Americanist, my theoretical and methodological framework includes dominant, historical narratives of racial oppression, nominal, binary political and social landscapes of the south and north, and epistemologies of race and theories on Black feminism and womanism. However, as I approached pre-1800 British literature on the history and culture of Scotland, I was unsure of how my methodological approach would inform my experience with the Boswell and Johnson travel journey. To my surprise, I found that the historical and cultural narratives of Scotland were profoundly shaped by the country’s colonial overtaking and the erasure of it’s tragic past; the recovery and excavation of Edinburgh’s historical and cultural past frames a reinterpretation of Scotland’s historical narrative and creates a nationalist, political and cultural identity.

It doesn’t take much difficulty to experience the presence of Edinburgh’s history; the sloping hills and resurrected castle atop the city serves as a metaphor for the upper, wealthy class raised above the lowly, degraded peasantry positioned at the lower rungs of society. The Mary King’s Close Tour tells the story of Edinburgh’s early history during the 1500-1600’s. The tight closes (alleys) lead to an underground world of the lower class. A lower caste in society guaranteed little sunlight, bad health and disease, and a dire quality of life. The sloping hills leading down to Nor Loch served as the pathway of sewage and human and household waste. The city gained notoriety across England for its pollution, and experienced the Bubonic Plague that eradicated over half of its population. The Old Town became a stain in Scotland’s history; an erasure of that history led to the physical covering and development of a new city atop an old, hoped-to-be-forgotten one. The historical tours of Edinburgh and Scotland reflect intentional acts of recovery; the reflections of these details seek to heal the collective memory of a history once denied and dominated by English rule. During our tours, we were informed of the long, tumultuous relationship between Scotland and England. Tour guides countered the dominant narrative of a Scotland indebted to England for financial security and cultural uplift. Instead, we were given a narrative of colonial rule, “ethnic cleansing,” and invasion. The declaration of this positionality created a sense of unity and pride of Scottish history and heritage. These narratives encouraged me to take a more critical and comparative look at the narratives of James Boswell and Samuel Johnson in A Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland and the Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides (Boswell as a native Scot, and Johnson as an Englishman). How does Johnson’s identity inform his travel narrative of Scotland? What language does Johnson use to describe the historical, physical, and cultural aspects of Scotland, and how did that color the minds of readers during that time? How does Boswell’s interpretation of Scotland vary from Johnson’s? These questions, coupled with the my experience in Scotland, presented me with a unique perspective of the influence of place and how the recovery of one’s past can inform iand even create a stronger sense of cultural identity.

JULIE’S RESPONSE

In the opening lines of A Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland, Samuel Johnson writes, “I had desired to visit the Hebrides, or Western Islands of Scotland, so long, that I scarcely remember how the wish was originally excited” (35). Being the only English person on the trip, I was the Samuel Johnson in the group who had lived next door to Scotland for most of my life and had never been. Like Johnson, I too knew very little about the Scotland I would encounter except for what I had read in books and what I had grown up to understand from those around me who had an English nationalistic perspective.

In his “Coriatachan in Sky” chapter, Johnson expresses his disappointment at coming “too late to see what [he] expected … The clans retain little now of their original character, their ferocity of temper is softened, their military ardour is extinguished, their dignity of independence is depressed, their contempt of government subdued, and their reverence for their chiefs abated” (73). Only 20 years or so had passed for Johnson since the British suppressed the last Jacobite rising—Johnson refers to it briefly as “the late conquest of their country” (73). According to one of our tour guides, the English crushed the Scots at the last Jacobite rising, barring any representation of Scottish nationalism henceforth. He called what the English did as nothing short of genocide. Johnson saw the aftermath of a nation stripped of all traces of its culture, yet he described what he observed with an objective reality. This was Johnson’s style, of course, but I wonder if the Scots today would criticize Johnson’s detached response as a mark of the writer’s Englishness.

Two hundred and fifty or so years later, bejeweled with my red coat and supporting an English accent, I found myself walking in the footsteps of Boswell and Johnson. I, too, was eager to experience the national manners of Scotland. Like Johnson, I found the Scots to be very hospitable, but had Johnson been alive today, his journal entries might look a little different in many other respects. Our second tour guide, for example, displayed strong nationalist sentiments and a fierce contempt for English politics. He talked about the Jacobite risings with an elegiac tone and slated the English for their treatment of the Scots after Bonnie Prince Charlie’s defeat in the mid-1700s. This same tour guide made me suddenly aware of why my red coat had gotten so much attention in the first few days, and I wanted to pack it away. For the first time in my life, I heard the history of the eighteenth-century conflict between the English and the Scottish from the perspective of a Scot and it was eye opening. The tour guide didn’t mean to make me feel uncomfortable. My narrow-minded English perspective of the conflict between England and Scotland made me feel uncomfortable. It took traveling to Scotland and encountering its people to learn that the Scots have their own version of history and their perspective is every bit as relevant as mine.

JACOB’S RESPONSE

This trip was very important for me, both in terms of transcript and personal growth. Unlike many of my fellow travelers, this trip marked my first plane ride and my first time outside of the southeast states. Therefore, in this blog, I want to talk about my growth internally. Experience is always subjective and even though my classmates and I went to the same places, what we each saw and felt was truly unique. So I will begin at the beginning: I can recall the nerves and butterflies that filled my stomach as I first walked onto the Delta plane at Hartsfield-Jackson. I had no idea what to expect, plus the keenest urge to watch Final Destination—morbid and masochistic—came over me the minute I found my seat. From there, I flew to DC, then to London and, after an unplanned 9-hour layover, finally to Edinburgh.

It was strange being so close to all these cities that I had never seen and yet, being unable to see them, even when only a glass wall stood between me and the unknown cities. While we all go through that moment of realization that we are not alone in this world, that our childish solipsism should be traded for the knowledge of a community far greater than we could ever have imagined, sitting in the London Heathrow international airport and hearing French, German, Spanish and English being used throughout the crowds so commonly closed the gap between what I’ve studied and reality. As a humanities scholar, I have always thought of myself as worldly, but what is bound between the covers of my books can never accurately grasp the sensuous, intimate exposure one gets when actually traveling.

When I started reading the course text, A Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland and The Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides by Samuel Johnson and James Boswell, the following struck me instantly,

In the morning we rose to perambulate a city, which only history shews to have once flourished, and surveyed the ruins of ancient magnificence, of which even the ruins cannot long be visible, unless care be taken to preserve the; and where is the pleasure of preserving such mournful memorials? They have been till very lately so much neglected, that every man carried away the stones who fancied that he wanted them. (Johnson 36, emphasis added)

This passage from Johnson picks up on a unique part of traveling: the need to prove that there was here. Too often we look to buildings and their cultural significance to give meaning to a place. A cathedral or court house makes an area, they are markers for directions. A statue, which abounded all throughout Edinburgh, make a statement and say that this spot is significant. Yet, as Johnson notes above, these structures decay. While care and preservation can hold off the ravages of time, we still urge ourselves to make memories and inscribe them onto something tangible. For me, that came in the form of sea glass found along the shore of Loch Ness.

As we all explored Loch Ness, possibly hoping to see the great monster, we lost track of each other. I drifted alone along the shore. I waded in the water, darker and deeper than I could have ever imagined. Even as an American, I grew up knowing that Loch Ness was a place where fog and tourists mixed, but the reality is far different. Its nestled among hills and mountains, with access to a canal and town. Ferries of people roam about its waters throughout the weekdays and ends, even far more when it is not during the off season. Listening to and watching the waters, I walked up the strand to an edge out of sight, almost forgotten. I sat on a stump, where ivy vines had grown round and lush green leaves covered the microcosm of organic life. Turning to the ground I looked for rocks to skip and noticed a frosted white color peaking through the rocks. It was the bottom of a bottle that had been broken somewhere near there, whose very chemistry had changed and mutated through years of tides coming in and out. Instantly, I felt the need to take it from its home on the beach, to keep it for myself—for my memories. In a way it embodied Johnson’s concept. It had an existence once that upon being neglected, ruined, it changed and degraded through time into something different. Something worth picking up and carrying home.

I chose to write on this experience because it was the moment that my mind clicked; my existence was bound in my memories and I bound my memories in this object. In the end, this blog cannot hold the amount of information that a single week in Scotland could give you. I never understood why the Germans call it Fernweh (far-sickness), until I came home and had to look back. The trip was amazing and the memories will be cherished for as long as I can remember them, but all it has done is ignite a fire to return and go further.

BOWIE’S RESPONSE

Nationality, Community, and the Commando Memorial at Spean Bridge

Three soldiers stand on a little hill near Achnacarry Castle, in the West Highlands; they glance out towards the mountains. “UNITED WE CONQUER,” reads an inscription below their feet. The Commando Memorial at Spean Bridge is dedicated, “In memory of the officers and men of the commandos who died in the Second World War 1939–1945.” As we with them look out to the remote and snow covered mountains, we read that “this country was their training ground.”

As we stood by the soldier’s statue, I thought of the tides of war that necessitated the barren and silent hills’ purity provide an environment to ready soldiers for battle. Human good and evil touches the furthest reaches of the world, loneliest mountains just as the fraught city. I once gave an interpretive talk, working for the National Park Service in Muir Woods National Monument, whose guiding question asked, “How is conservation essential for world peace?” Muir Woods was the site of an early meeting of delegates to the United Nations in 1945 to honor the memory of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who before his death had become convinced conservation would be necessary to preserve world peace. Harold Ickes, his secretary of the Interior, first passed the idea to hold a meeting in the Redwoods to Roosevelt in a letter:

Not only would this focus attention upon this nation’s interest in preserving these mighty trees for posterity, but here in such a ‘temple of peace’ the delegates would gain a perspective and sense of time that could be obtained nowhere in America better than in a forest. Muir Woods is a cathedral, the pillars of which have stood through much of recorded human history. Many of these trees were standing when Magna Carta was written. The outermost of their growth rings are contemporary with World War II and the Atlantic Charter.

(National Park Service)

Surrounded by the mountains of the Highlands now scored with the memory of the Commandos, I thought of the ways that something distant can be near, just as what’s immediate can be distant. The history of World War Two, which brought one of my grandfathers from America to France, should teach us isolation is an illusion. Madeleine Albright, in a New York Times op-ed appearing April 6th, 2018, writes that Fascism, though humans may have thought it dead, is on the move around the world. She argues America’s turn away from world leadership in the promotion of democracy and humanitarianism, encapsulated in the person and actions of Donald Trump, paves a way for the abuses of Fascist and totalitarian governments.

While western society privileges individualism over community, I have come to believe in the intense interconnection of the two. Our excellent tour guides on the voyage both emphasized the pride they took in the Scottish nation, and their wish for its independence. Yet their manners indicated the independence in which they took pride was one that welcomed strangers with dignity and kindness. I received a welcome in equal measure from Scots throughout our journey. Though one lives and dwells in one’s home country, it behooves us to recognize the community we belong to is a human one, as traveling reminds me.

Works Cited

Albright, Madeleine. “Will We Stop Trump Before it’s Too Late?” The New York Times, April 6th, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/06/opinion/sunday/trump-fascism-madeleine-albright.html. Accessed April 6th, 2018.

Searle, Mike. “CC BY-SA 2.0.” https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9952199. Accessed April 6th, 2018.

Stevens, Arthur. “CC BY-SA 2.0” https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9952275. Accessed April 6th, 2018.

“The United Nations War Memorial at Muir Woods.” National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/goga/learn/historyculture/un-at-muir-woods.htm. Accessed April 5th, 2018.

KATHRYN’S RESPONSE

A Sojourn to the Glasgow Women’s Library

Kathryn Dean

On our last day in Glasgow, I was keeping a promise I’d made to myself four years prior.

In 2014, I visited some friends in Ayr, and during that trip, we got a chance to go to Glasgow very briefly. All I saw of the city was the Kelvingrove (a fantastic museum) and the Riverside Museum (a place I was thrilled to explore, as someone interested in transportation). However, it was at the Riverside Museum that I picked up a brochure about the Glasgow Women’s Library. I was devastated I didn’t have time to visit.

The rest of our group had headed off to see a medieval cathedral, a place I had some interest in seeing, but I knew I had to keep this promise to myself. I had to go to the library. I took a short train journey to Bridgeton station around 10:00 am. It was a quiet station; only one other person got off the train with me. I stood under a large structure beside the train station known as the Bridgeton Umbrella (http://www.bbc.co.uk/scotland/landscapes/bridgeton/) and tried to get my bearings. As a person who’s directionally challenged, I constantly need to check a map to make sure I’m in the right place. The library was right around the corner, but I walked in a couple of circles until I found it.

The Glasgow Women’s Library (GWL) is in a quiet, seemingly residential neighborhood. In fact, I nearly passed it by before I realized that there was a sign on the front of the building. As I turned the corner, I saw more signs that I was in the right place.

When I walked in to the library, I was greeted by two volunteers at the desk, both of whom appeared to be in their twenties. I told them it was my first time at the library and they were very welcoming. They even gave me a small tour of the library, showing me an exhibition space, discussing their collections, their collections, and recounting the history of the library.

The current building that Glasgow Women’s Library occupies is an original Carnegie library built in 1906. Until recently, it housed the Bridgeton Public Library, but when it moved to a new building, GWL had an opportunity to move into the space. The carpet, a distinct and colorful schoolhouse pattern, is unique to this space; it was made by a local mill. This, despite the extensive renovations that GWL did to the building when they acquired it in 2013, remains as a gesture toward the history of this building as a central place in the community.

Before 2013, GWL had been itinerant for a while. It was originally founded in 1991, a direct response to Glasgow being named City of Culture in 1990. There was a lack of women’s stories represented in Glasgow, activists noted, and in order to rectify this, they created an organization focused on women’s history in Glasgow, which eventually led to the creation of the library.

While visiting GWL, I was alternatively reminded of Charis, Atlanta’s feminist bookstore, and the GSU Archives for Women and Gender. In a way, GWL is the perfect meeting of these two places; it’s a feminist gathering space, offering community events and services, but it’s also a place that houses archives, ephemera, history.

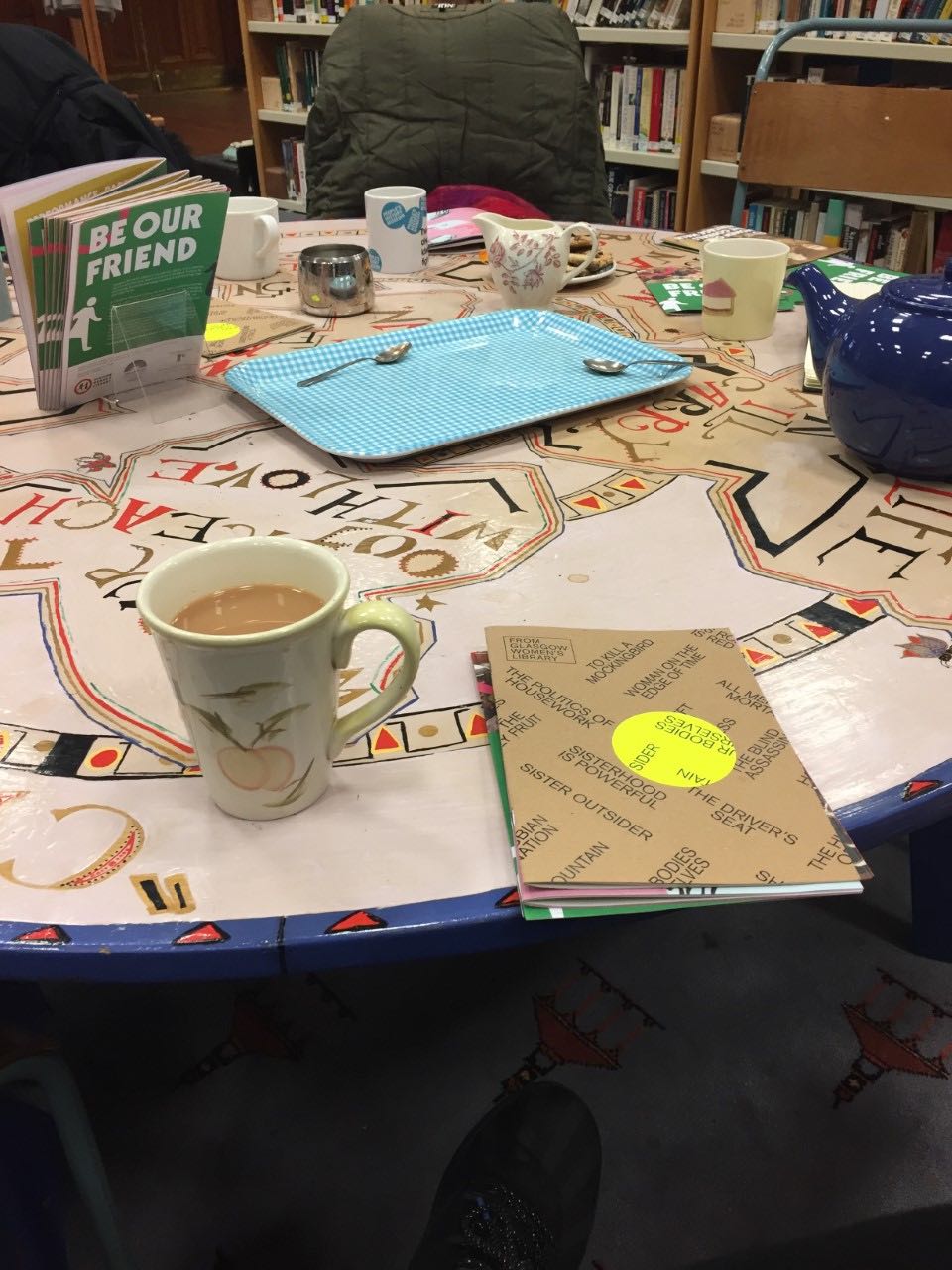

My tour guide showed me the small reading room, then asked if I’d like a cup of tea or coffee. I was in desperate need of a hot drink by this time, having been trudging through the gloomy cold all morning. I happily accepted a cup of tea (milk only, no sugar) and sat down at a large table where some volunteers were having a meeting. They gloriously ignored me, not asking me to leave or giving me an odd look, just accepting my presence in this space. It felt almost transgressive to be drinking tea in the library.

“All the books here are by women, or about women, if they’re biographies,” my tour guide had told me. I was impressed by the number of books I was instantly interested in, books that I’d never heard of before and that lined up perfectly with my interests.

While I was there, the library was preparing for their weekly Story Café (https://womenslibrary.org.uk/event/story-cafe-special-spring-stories/), so more and more people were arriving as I prepared to leave.This is one of several weekly community events that the library hosts. The library also hosts authors, creative writing workshops, walking tours, and more. I was fascinated by the community engagement that this library had created.

But I only had an hour, so I couldn’t stay. I wished that I could stay longer and learn more about how this place works day to day. I felt such a pull toward this place that I wanted to stay involved. Though I couldn’t borrow a book since I was leaving Glasgow that day, I joined the library in the hopes that one day, I’d return.